January 15, 2016

When you think of the many apparel options that are available for embellishment, a traditional Japanese kimono probably doesn’t immediately come to mind.

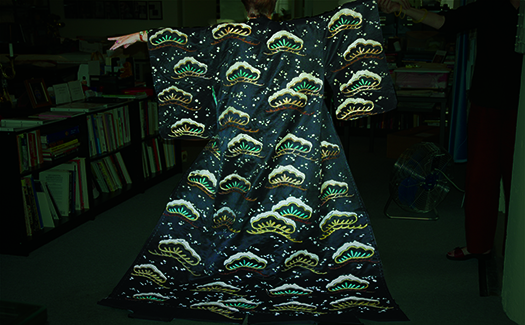

However, Colleen Atwood, costume designer for the motion picture “Memoirs of a Geisha,” requested such an embellishment on this type of garment from Long Island City, N.Y.-based embroidery atelier Penn & Fletcher some 11 years ago. A specialty house founded in 1986 that does work for high-end clients, Atwood chose Penn & Fletcher because of its reputation.

“My belief,” says Penn & Fletcher owner Ernie Smith, “is that if you need us, you are probably at a stage in your career where you have already come across us.”

To the credit of Atwood and the 15 artisans who all took part in the creation of the kimonos used in the film, “Memoirs of a Geisha” was nominated for six Academy Awards and won four, including for best cinematography and costume design. The kimonos show what the designer wanted to convey about each character. Designs were done specifically for each geisha. Along with needing to be unique and revealing, each robe’s embellishment had to be durable.

“Costumes are like uniforms,” Smith says. “They have to withstand a lot of wear and tear. They are worn non-stop for months during a shoot.”

Production Details

The process began with a remnant of a pattern. The character Hatsumomo’s black, chinchilla-collared winter coat reportedly is one of Atwood’s favorites.

She explains how the process began: “I took the pattern off a vintage piece I found in London, moved it around and had it re-embroidered on a similar kind of silk,” she says. “Then [I] added the fur and the velvet lining, which is not something they did in Japan then. It’s a very made-up costume — a real geisha would never wear anything that flashy. But it was good fun, and I just thought it was beautiful.”

The production began with Penn & Fletcher duplicating the design in sections, pasting up positions of the embroidery and getting approval. The kimono is a combination of machine, hand and hand-guided machine embroidery. It was digitized by master digitizer Alex Herrera as individual files and then positioned on the garment as it was created.

Classic Rayon #40 thread and a #75/11 needle was used on one head of a 12-head Barudan machine for the machine embroidery portion of the designs. The thick gold embellishment is hand-applied gimp, whose size was determined by the number of threads in its core. The brown, three-thread metallic branch was done with a hand-guided embroidery machine that uses a hook needle to embed the chain stitch in the cord as it sews.

The fabric was a stable black silk satin that didn’t require backing. The white stitches on the black kimono are a novelty fill; the blue in the clouds is a satin stitch.

For the rust-colored kimono, flowers and leaves were created in satin stitches prior to production, and placement of each petal was hand chosen.

The process by which designs are duplicated and then arranged onto a unique garment such as a kimono is fairly complex. Patterns are computer generated using proprietary software versions of Adobe Photoshop and Illustrator. They are then sent to the art department, where the printed patterns are transferred to vellum using a perforating machine, fluorescent (cleanable) wax and black light. With this method, little to no lasting marks are made on the final fabric until the designs are stitched. This allows for no mistakes, since the fabrics came directly from the costume designer.

Practical Applications

How does this exotic, customized approach to apparel embellishment translate to the everyday?

Take denim jackets. The alternative technique of individually placing a design can be achieved more traditionally using a clamping hoop or stick-on backing (see “Other Backing Options”). Using the jacket as your design space and printing several copies of a design’s run sheet, you can arrange and re-arrange design placement on the jacket in order to accomplish something unique and personalized.

When not creating unique pieces for stage, film, ballet and opera — all of which accounts for about 20% of Penn & Fletcher’s embroidery work — the firm works with interior designers, architects and house museums to create unique home décor or re-create embroidered pieces for small, private museums.

“Textiles will last only 100 years under the best of circumstances,” Smith says. “In most cases, the embroidery will outlast the fabric.”

The firm currently is re-creating embroidered chair pieces for Olana, the Hudson, N.Y. home built by Frederic Church in 1872.

Alice Wolf is the marketing communications director for Madeira USA. She began doing marketing and public relations for the art industry in New York, then migrated north to Madeira’s New Hampshire headquarters. For more information or to comment on this article, email Alice at awolf@madeirausa.com.

July 28, 2023 | Design + Digitizing

Very few things in life stand the test of time. As natural as the ebb and flow of evolution, most seemingly universal customs are founded and practiced with vigor, only to fade away with a whisper as the years tick by.

FULL STORY

August 16, 2022 | Design + Digitizing

With this month’s On Design, we travel deep into the jungles of Central Mexico, harkening back to an ancient time where the Aztecs roamed the earth whilst building a formidable empire.

FULL STORY